Introduction: A Shifting Global Economic Center of Gravity

China’s rise over the past two decades has fundamentally reshaped the global economic order. Once a peripheral player, China has become the world’s second-largest economy and a vital engine of global growth. Its massive consumer base, manufacturing prowess, and influence in commodity markets have made it an indispensable pillar of the international financial system. However, in 2025, signs of deceleration in China’s economy are flashing bright red. From sputtering growth numbers to a deepening real estate crisis and worsening demographic pressures, the world is watching closely. The key question is whether China’s economic slowdown poses the most significant risk to global markets this year—or whether fears are overblown. This article examines the structural and cyclical dimensions of China’s economic troubles, explores the transmission channels to other markets, and assesses the broader implications for global investors and policymakers.

China’s Growth Data: A Tale of Deceleration

Official data from Beijing reveals a troubling trajectory for economic growth in 2025. GDP growth in the first quarter slowed to just 4.2%, below the government’s 5% target. Industrial production has weakened, retail sales have missed forecasts, and exports—long the bedrock of China’s growth—have shown inconsistent recovery patterns amid global demand weakness. Youth unemployment remains elevated, and consumer confidence has yet to fully rebound despite policy stimulus. Beijing has launched a flurry of supportive measures, including interest rate cuts, tax incentives for businesses, and infrastructure spending. Yet, these interventions appear insufficient to reverse the deeper structural forces at play. Among them, China’s aging population and declining birth rates are reducing the long-term labor force and straining the pension system. Productivity growth has also stalled as the country grapples with overcapacity in traditional industries and slow gains in innovation. The decoupling between private sector activity and state-driven investment highlights misalignments in resource allocation and policy direction. The shadow of COVID-era disruptions and prolonged lockdowns still lingers in the domestic services sector, leaving scars on consumption patterns and household risk appetite. Overall, the slowdown in China is not merely a cyclical dip—it represents a longer-term shift that will reshape global capital flows and economic planning.

The Real Estate Crisis: Systemic Risk or Contained Collapse?

Arguably the most visible and immediate threat to China’s economic health is its real estate crisis. Once a powerful growth engine contributing nearly 30% of GDP when accounting for related industries, the property sector is now a drag on the economy. Major developers like Evergrande and Country Garden have defaulted on debt, and construction activity has plummeted. Home prices are falling across both tier-one cities and regional markets, eroding household wealth and confidence. Despite multiple rounds of policy easing—including mortgage rate cuts, down payment reductions, and relaxed purchase restrictions—housing demand remains tepid. Local governments, heavily reliant on land sales for revenue, face budgetary strains, further limiting their ability to stimulate growth. Moreover, the mortgage boycotts seen in 2023-2024 revealed a dangerous breach of trust between developers, banks, and consumers. The unfinished housing crisis has become both a financial and social liability. Banks with large exposures to real estate loans face rising non-performing assets, though state support has thus far avoided a full-blown banking crisis. Nonetheless, the drag on growth is substantial. The government’s “common prosperity” drive and its efforts to reduce speculative bubbles have led to a deliberate cooling of the property sector, but the transition is proving painful. Without a credible and comprehensive restructuring strategy, the real estate crisis threatens to undermine not only GDP growth but also financial stability.

Spillover Effects: Emerging Markets on the Line

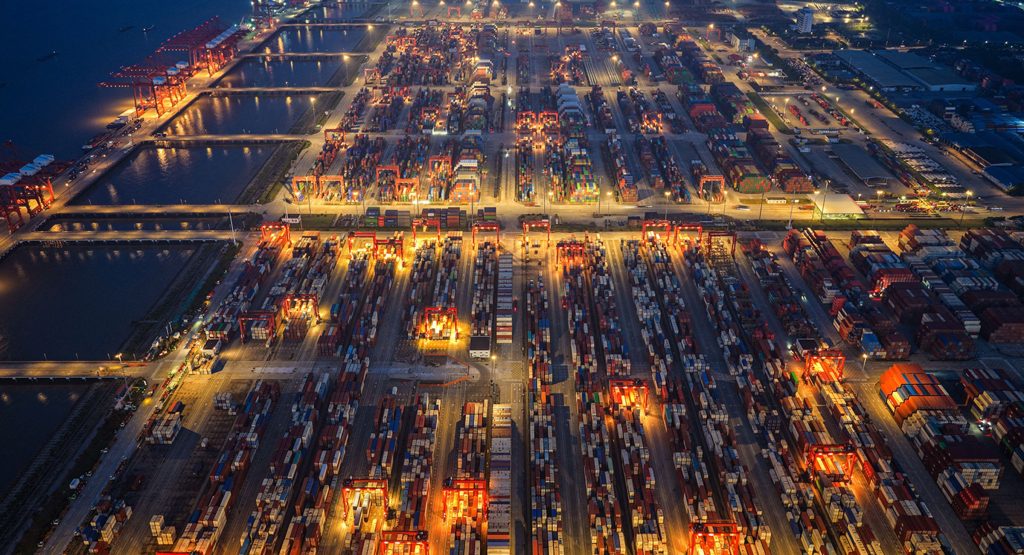

China’s slowdown does not occur in isolation. Its ripple effects are already being felt across emerging markets, many of which depend heavily on Chinese demand for exports, investment, and tourism. Countries like Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which supply raw materials from iron ore and coal to palm oil and copper, are seeing declining trade volumes and commodity prices. The IMF has flagged risks to developing economies that are “China-linked” as especially acute in 2025. Latin American countries that rode the wave of China’s industrialization now face fiscal and balance of payment challenges as export revenues falter. African nations that relied on Chinese infrastructure investment through the Belt and Road Initiative are also seeing a slowdown in project rollouts and financing. Currency markets have reflected these stresses, with many emerging market currencies depreciating amid capital outflows and declining confidence. Sovereign spreads have widened, particularly for frontier markets with high external debt exposure. Meanwhile, global commodity prices—once buoyed by insatiable Chinese demand—have come under pressure. Oil prices have remained range-bound despite geopolitical tensions, partly due to lower Chinese industrial activity. Base metals like copper and aluminum have seen sluggish demand growth, reducing earnings for commodity exporters and mining companies. The prospect of reduced Chinese investment in global supply chains and foreign direct investment projects also weighs heavily on future development paths.

Financial Markets: China Contagion or Controlled Decoupling?

Global equity and bond markets are parsing every data release from China for clues about systemic risk. Chinese equities have underperformed global benchmarks, with the Hang Seng Index struggling to regain momentum and mainland A-shares suffering from low investor participation. Foreign investors have withdrawn funds from Chinese ETFs and mutual funds amid concerns about regulatory unpredictability, policy opacity, and weakening earnings. On Wall Street, U.S. and European stocks have proven more resilient but show increased volatility when China’s data disappoints. Global fund managers remain wary of direct exposure to Chinese corporates, particularly those in real estate, banking, and technology sectors. Bond markets tell a more nuanced story. Yields on Chinese government bonds have remained stable due to domestic demand and state control over the financial system. However, spreads on Chinese high-yield bonds—especially those linked to real estate—have widened sharply, reflecting investor unease. International banks and asset managers with significant Chinese exposure are reevaluating risk models and adjusting portfolios. Hedge funds are deploying short strategies on the yuan and China-linked ETFs, while institutional investors seek safe havens in U.S. Treasuries and gold. The idea of “China decoupling” has gained traction, with global capital rebalancing towards India, Vietnam, and other Southeast Asian economies seen as more stable and demographically favorable. Yet, the sheer size and integration of China in global trade, finance, and technology means that a complete decoupling is neither realistic nor painless.

Policymaker Response: Navigating the Storm

Beijing faces a daunting balancing act—revive growth without reigniting bubbles or undermining structural reforms. The People’s Bank of China has limited room to maneuver given already low interest rates and the risk of capital flight. Fiscal stimulus has focused on infrastructure, but questions remain about efficiency and debt sustainability. Premier Li Qiang has signaled a shift toward consumption-driven growth, but this transition requires deep reforms in social safety nets, labor mobility, and income distribution. Meanwhile, regulatory crackdowns on tech firms and private education have created a trust deficit with the private sector. Internationally, China is trying to reassure investors through diplomatic overtures, new trade agreements, and softened rhetoric on geopolitical disputes. However, tensions with the U.S. over technology, Taiwan, and trade remain elevated, adding another layer of uncertainty. The G20 and IMF have called for coordinated responses to mitigate systemic risk from China’s slowdown, but global policy coordination remains fragmented. Central banks in developed markets must also grapple with the deflationary impulse from China, which could complicate inflation-targeting strategies already under strain.

Investor Strategies: Navigating a China-Centric Risk Landscape

For global investors, the key is not whether China slows—it’s how to position portfolios in light of it. Some asset managers advocate for underweighting China while overweighting beneficiaries of supply chain diversification such as India, Mexico, and Indonesia. Others suggest selective exposure to Chinese sectors tied to domestic consumption, green energy, and technology that align with long-term policy goals. Commodities traders are turning cautious on industrial metals but remain optimistic about agricultural inputs and lithium, where demand dynamics are less China-dependent. In equities, large-cap U.S. firms with minimal China exposure have become relative safe havens. Currency traders are watching the renminbi closely for signs of devaluation pressure, which could have spillover effects across Asia. Credit investors are trimming exposure to Chinese high yield and pivoting to sovereign debt in commodity-rich but politically stable countries. Private equity and venture capital firms are shifting new investments toward emerging tech hubs outside China, although legacy investments remain trapped in regulatory uncertainty. Overall, the new normal for global investors is one of higher risk premiums, slower capital velocity, and greater macro scrutiny—all anchored to the outlook from Beijing.

Conclusion: The Biggest Risk—or the Most Visible One?

Is China’s economic slowdown the single biggest threat to global markets in 2025? It may be the most visible and structurally significant risk—but it is not the only one. The confluence of global monetary tightening, geopolitical flashpoints, and climate-related disruptions also loom large. However, what sets China’s slowdown apart is its sheer systemic reach—impacting everything from commodity prices and supply chains to equity risk premiums and development finance. The narrative of China as the inexhaustible growth engine is being redefined, and with it, the assumptions that underpinned decades of investment strategy. Whether China can execute a controlled economic transition or spirals into a prolonged stagnation will shape not just regional outcomes, but the entire global financial landscape. For now, caution reigns, but so too does hope that policy pragmatism, structural reform, and global cooperation can steer the world’s second-largest economy—and the markets it anchors—toward a more stable future.